Measuring impact and global influence

The significance of MEL for policy influence

Introduction

Literature on how to monitor, evaluate and learn about policy influence is abundant. However, because influencing policy is such a complex, long-term and unpredictable process, some researchers and practitioners wonder whether it’s worth investing energy and resources into a systematic assessment of policy influencing efforts. In addition, some monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) activities can arouse apprehension, especially if they are perceived as an accountability exercise or a control mechanism.

Our view is that incorporating MEL into the daily life of any organisation is well worth it. A smart and proportionate use of MEL tools, especially as part of a well-thought-out MEL plan, can help organisations to:

- Reflect on and enhance the influence of their research on public policy.

- Satisfy their (and their donors’) interest in evidencing the uptake of research in policy.

- Build their reputation and visibility, and attract more support for their work.

- Generate valuable knowledge for all members of the organisation.

- Reorganise existing processes for data collection so that they can be useful for real MEL purposes, and discard processes and data that are not useful.

Why develop a MEL system?

Being clear about why a think tank wants to do an evaluation (and MEL more widely) is a key first step.

Consider the following questions about a think tank:

- Does the think tank need to inform its donors and key stakeholders on the impact it is having?

- Does the think tank want to strengthen and improve the way in which it implements projects?

- Does the think tank want to make better decisions on the organisation’s strategic direction and/or its programmes?

- Does the think tank want its staff to have more and better knowledge to improve the way it goes about influencing policy?

- Does the think tank want to empower its members through greater consensus and commitment to the objectives?

These objectives – and the reasons for undertaking MEL activities – can be more or less applicable to organisations depending on their individual characteristics, experience, leadership interests and values, and so on. The important thing is for an organisation to be clear about its own reasons for the MEL effort, since the strategies and methodology chosen will vary according to the type of knowledge that is needed and how it will be used.

Note that there can be arguments against too much MEL. Here are 5 reasons why a think tank might choose not to undertake Monitoring and Evaluation (or to avoid doing too much of it) — especially when it becomes a compliance-heavy exercise rather than a learning tool:

-

It can become a major time-sink with low returns: MEL often has a “bad reputation” because it’s experienced as difficult, boring, and slow, with staff pulling information together for ages—sometimes only because a donor asks or a board meeting is coming.

-

The metrics can be misleading (giving false confidence or false alarms): OTT notes that “technological data can be misleading”—even basic things like views, counts, and unique users can be distorted by how platforms measure activity. If you over-rely on these numbers, you can end up “proving” things that aren’t true.

-

You may measure the wrong things and conclude you have “no impact”: OTT’s comms/MEL guidance warns that what you measure must match how you seek influence. For instance, if you’re a convenor, heavy media monitoring might miss your contribution (journalists quote speakers, not the organisation that created the space), making it look like you achieved nothing.

-

It can turn into funder-driven accountability theatre, crowding out learning: OTT explicitly cautions that using monitoring data only to satisfy donor requirements or annual reports is a “missed opportunity”—because the main benefit should be learning and adaptation. Relatedly, OTT observes how some think tanks may end up worrying more about accountability to foreign funders than to domestic audiences, and how “bottom-up learning” can start to feel like evaluation done only for accountability.

-

It can reinforce the “myth of influence” and encourage over-claiming (or even distort research choices): OTT argues that think tanks often tell neat stories of policy influence, but when scrutinised these claims “fall short,” because many other forces shape decisions (agendas, interests, public opinion, luck, etc.). Over-investing in M&E designed to “prove influence” can incentivise storytelling over truth. OTT also warns (in the evidence-policy debate) that pressure for “uptake” can push researchers toward “policy-based evidence making”—a risk when measurement becomes a driver of what gets researched and said.

Different purposes and reasons for MEL will require different approaches to the activities. For example, a MEL framework focused on learning what works and what needs to change will pay attention to ‘why’ the initiative was developed and ‘for whom’, with some concentration on ‘what conditions’ are needed to influence policy. For this purpose, drawing on methods like developmental or realist evaluation can be useful. But when conducting MEL for donor reporting, for example, the focus will be on the question of ‘if’ something worked. It will be geared towards demonstrating success and evidencing change.

Assessing what matters: Is it possible to monitor and evaluate policy influence?

Assessing the impact of research on policy is complex – and it’s important to acknowledge the inherent limitations and challenges of trying to do so. Research and evidence are just one of many inputs, and their impact depends on how they compete with other ideas and other influencing efforts. That’s why linear or rational models – where research leads directly to solutions that policymakers adopt – are too simplistic. A more intricate model that considers the interactions among various stakeholders and external factors reveals the complex realities of multiple decision-making arenas.

What aspects of policy influence efforts can be effectively assessed? To address this key question, it’s crucial to first broaden the definition of ‘success’ beyond the strict achievement of policy change. Mendizabal (2013c) offers useful discussion points for defining the broader scope of policy influence:

- Research uptake is not always ‘up’. Not all ideas flow ‘upwards’ to policymakers. For most researchers, the most immediate audience is other researchers. Ideas take time to develop, and researchers need to share them with their peers first. As they do so, preliminary ideas, findings, research methods, tools, and so on flow in both (or multiple) directions. ‘Uptake’, therefore, may very well be ‘sidetake’ – researchers sharing with other researchers. By the same token, it could also be ‘downtake’. Much research is directed not at high-level political decision-makers but at the public (for instance, public health information) or practitioners (such as management advice and manuals).

- Uptake (or sidetake or downtake) is unlikely to be about research findings alone. If the findings were all one cared about, research outputs would not be more than a few paragraphs long. Getting there is as important as the findings. Methods, tools, the data sets collected, the analyses undertaken, and so on, matter as well and may be subject to uptake. The research process is important too, because it helps maintain the quality of the conversation between the different participants of the policy process. In essence, policymakers need to understand where ideas come from.

- Replication is uptake too (and so is inspiration). Consider the inter-generational transfer of skills. Much of the research conducted in universities and think tanks can be used to train new generations of researchers or advance a discipline or idea – and this counts as uptake. Writing a macroeconomics textbook or a new introduction to a sociology book, for example, is as important as producing a policy brief. The students who benefit from these research outputs are likely to have an impact on politics and policy in the future – something that is nearly impossible to measure in the here and now.

- It is not just about making policy recommendations. The purpose of research is not only to recommend action. Researchers, including those in think tanks, often influence by helping decision-makers understand issues rather than pushing for specific actions. To gauge research uptake, it’s essential to consider all the functions of think tanks: agenda-setting, issue explanation, popularising ideas, educating the elite, debate facilitation, critical thinking development, public institution assessment, and so on.

- Dismissal is uptake too. Uptake is often equated with doing what the paper recommends. But research does not tell anyone what to do; it informs stakeholders about situations, alternatives, and future effects rather than dictating actions. It’s up to policymakers to make the decisions, and researchers (and donors) shouldn’t anticipate that research alone will drive change.

- Uptake is ‘good’ only when the process is traceable. Good uptake happens when good ideas, practices, and people are incorporated into a replicable and observable decision-making process. The goal should be good decision-making capacities, not just good decisions. The latter, without the former, could be nothing more than luck. And in that context, bad decisions are just as likely as – if not more likely than – good ones. Bad decisions can be lived with – but poor decision-making processes are unacceptable. And worse still is keeping these decision-making processes out of sight.

There’s extensive literature on evidence in policy-making, and various frameworks assess evidence-informed policymaking (EIPM) by examining both supply and demand factors, including policymakers’ ability to use evidence, and evidence quality, relevance, and timeliness. Think tanks typically operate on the supply or intermediary side, collecting or translating evidence for policymakers. A MEL framework for think tanks should therefore emphasise these EIPM aspects, but also consider other factors influencing the outcomes of their engagement with policymakers.

The following video offers some additional insights into the opportunities and challenges involved in measuring impact:

Six key areas for MEL

Pasanen and Shaxson’s (2016) guidance note summarises six areas of MEL for knowledge institutions, structured around six key questions that organisations should ask:

- Strategy and direction: Is the organisation doing the right thing? This component focuses on the start of the project and is monitored and evaluated at regular intervals. It ensures that an organisation’s strategies are on track and adaptable to changing circumstances.

- Management and governance: Is the plan being implemented in the most effective way? This too should be assessed regularly and focus on the effectiveness of management and governance structures in implementing the plan.

- Outputs: Are the outputs the most appropriate for the target audience and do they meet the required standards? This is about monitoring and evaluating specific outputs, such as a research paper or a workshop.

- Uptake: Are people accessing and sharing the outputs? This involves evaluating the accessibility and sharing of produced outputs among the target audience.

- Outcomes and impacts: What effects are being generated by the think tank’s work? Is it contributing towards any change? This component forms the core of evaluation work and can be summarised by the key question of ‘so what?’.

- Context: How do political, economic, social and organisational changes affect the work and outcomes of the organisation? This should be monitored at regular intervals, especially before a project starts and at its end.

A seven dimension, missing in most MEL discussions, concerns think tanks’ bottom line: income, expenses, margins, reserves. If think tanks are not financially sustainable – does it matter if they have impact?

See: Finance and operations module

Building a framework for effective policy influence

Developing a good theory of change

The first step of developing a good MEL framework is to identify a clear and explicit theory of change, including the desired policy impacts and underlying assumptions. Clarity is crucial for directing evaluations towards organisational priorities and testing the theory’s assumptions.

The RAPID Outcome Mapping Approach (ROMA) (ODI, 2014) offers guidelines for think tanks to shape their theory of change and accompanying MEL framework. It explores various types of change that a policy-influencing strategy can target and suggests the creation of key policy-influencing parameters. These could be changes in discourse among policy actors and commentators (e.g., what language are they using), improvements in policy-making procedures and processes, changes (or no changes) in policy content, and changes in behaviour for effective implementation (see ODI 2014, page 27).

Think tanks should identify the changes they want to make, the specific activities involved, and who the changes are intended for – the latter of which should be done through a stakeholder mapping exercise, as outlined in the ROMA guide’s Interest and Influence Matrix (also referred to as the Alignment, Interest and Influence Matrix). When linking activities to the desired results, it’s crucial to clearly state the assumptions so that they can be tested.

After identifying the desired changes, intervention target groups, and associated activities, the next step is to devise data collection and analysis methodologies. These methodologies are essential for discerning whether the intended changes are taking place, and need to take into account both monitoring and evaluative aspects. At this point, it’s crucial to distinguish between monitoring and evaluation.

Monitoring involves the data you collect on an ongoing/regular basis and is best suited for tracking incremental changes. Evaluation, on the other hand, focuses on broader, medium- to long-term transformations, and asks what your work as a think tank has contributed to these changes. Outcome mapping combines strategy design with monitoring and evaluation and is a valuable tool for both planning and assessing the effectiveness and impact of your work.

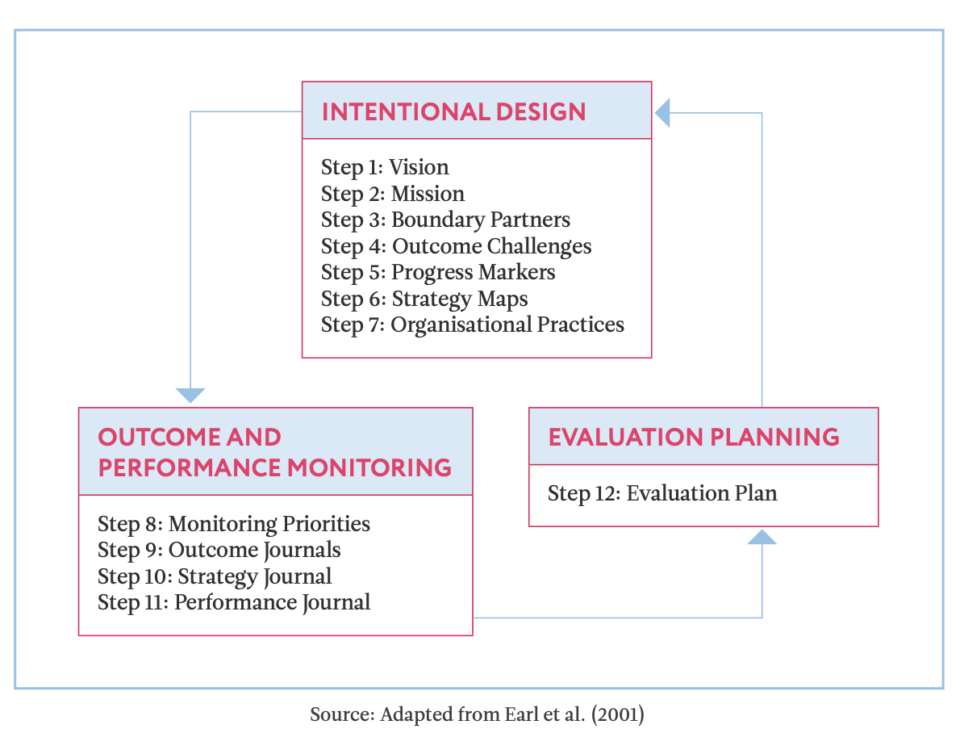

Outcome mapping is a good framework to use to guide MEL work. As outcome and performance monitoring are built into the approach, it’s a good tool both to plan for impactful policy influence and to actually monitor and measure policy impact.

Three stages of Outcome Mapping

Collecting data on evidence use

Developing appropriate data collection tools to monitor evidence use in public policy can be complex. Policymakers themselves may not always recognise their use of evidence due to misconceptions about what is actually meant by ‘evidence’. Furthermore, policy documents may not always cite the evidence used, and, in any case, policy changes may not always be reflected in a single document. It’s important to think about how to get meaningful information when devising evaluation questions and to triangulate data.

Additionally, it’s important to understand why a policymaker is using or not using a particular piece of evidence at a particular time. It can also help to identify barriers to evidence use – such as lack of awareness, competing values, resource shortages, promises to constituents, or general public discourse – in order to understand where we need to direct our efforts. Likewise, it’s crucial to understand when and how evidence is being used – for example, to better understand an issue/problem, to change policy discourse, or even to retrospectively justify decisions that have already been made. Davies et al. (2005) have outlined a taxonomy of evidence uses, categorising them as either ‘conceptual uses’ (for changing people’s knowledge, attitudes or understanding around a policy issue) or ‘instrumental uses’ (for driving a change in practice, policy or behaviour). Others have broken these down into further categories, such as political use or symbolic use.

The evaluation of evidence use typically relies on two methods: (1) interviews with subjects involved in the policy process or (2) a qualitative review of policy documents, followed by a conversation with decision-makers to reconstruct the decision-making process and the role of evidence (Nesta, 2019). While there are different tools and methods for MEL on evidence use, it’s important to be aware of the limitations of each, to find ways to triangulate data collection to mitigate those limitations, and to combine tools where necessary.

LESSONS FROM B2B MARKETING

Recognising that the policy process is complex and non-linear, Nesta (2019) offers an alternative way to measure evidence uptake that borrows from private sector business-to-business (B2B) marketing approaches:

Persona mapping: mapping targets organisations and their system of decision-making, including the decision-makers and supporting actors. Typologies of these personas are created with detailed accounts to understand their attitudes, fears, behaviours and objections.

Customer journey mapping: mapping the journey each persona might take to reach a decision. The mapping should be as detailed as possible, covering elements like pre-conceptions about the service or product, media consumption habits that could influence a persona’s attitudes about the service/product, the role of competitors, and the persona’s contribution to the decision-making process.

Touch-point analysis: identify interaction points between the decision-maker and the think tank, enabling the creation of targeted KPIs for measuring engagement in relevant situations.

Other considerations

Who should participate in MEL and who will benefit? Who will use the findings, and how? Michael Quinn Patton’s (2021) utilisation-focused evaluation framework emphasises that evaluations should be measured by their utility and actual use. Evaluators should facilitate the [evaluative] process, while carefully considering how every step will impact utilisation of the findings. It’s not only essential to consider how others will benefit from the results, but also how they will be involved (or not) throughout the entire process, including reflecting on it for learning and decision-making.

Three key questions should be addressed when designing a MEL framework:

- What types of information and knowledge would help the think tank to become better at informing policy with its research?

- What does the think tank need to learn?

- Who needs this information?

Participation is crucial. MEL initiatives should engage stakeholders from the outset, from conceptualisation to design, fostering a culture where learning is prized as much as accountability.

Involving others also presents an opportunity to identify ongoing issues and challenges faced by staff, which MEL practices can address. Staff are more likely to embrace a new system when they recognise its relevance to their work. Beyond donor compliance or showcasing success, MEL should inspire staff buy-in and maintain the MEL system effectively.

Engaging others can lead to insightful outcomes. For instance, a think tank’s staff, while contemplating MEL, may recognise the need to revise their project-design approach. This scenario is common. The consideration of MEL dimensions often prompts a re-evaluation of planning strategies, results, and project alignment with programme or organisational objectives.

References and further reading

- Befani, B., D’Errico, S., Booker, F. and Giuliani, A. (2016). Clearing the fog: New tools for improving the credibility of impact claims.

- Better Evaluation. (2013). Outcome mapping.

- Carden, F. (2009). Knowledge to Policy: Making the Most of Development Research.

- CIPPEC (n.d.) Toolkit No. 1. Why should we monitor and evaluate policy influence? From the series: How can we monitor and evaluate policy influence?

- Davies, H. T. O., Nutley, S. and Walter, I. (2005). Assessing the impact of social science research: conceptual, methodological and practical issues.

- Davis, H. (2005). What works to promote evidence-based practice? A cross-sector review.

- Earl et al. (2001) Outcome mapping: Building learning and reflection into development programs. Ottawa: IDRC.

- Lomofsky, D., Mendizabal, E., Knezovich, J. (2017). Monitoring, evaluation and learning digital dashboard for IFAD.

- Lucas, S. (2017) 6 ways think tanks can overcome angst about impact.

- Mendizabal, E. (2013). Research uptake: what is it and can it be measured?

- Mendizabal, E. (2013a). A monitoring and evaluation activity for all think tanks: Ask what explains your reach.

- Mendizabal, E. (2013b). Monitoring and evaluation: Lessons from Latin American think tanks.

- Mendizabal, E. (2014) Monitoring and Evaluation for Management.

- Nesta (2019). Measuring Evidence Impact.

- ODI (2014). ROMA: A guide to policy engagement and influence.

- On Think Tanks Monitoring, evaluation and learning for think tanks series.

- Pasanen, T. and Shaxson L. (2016). How to design a monitoring and evaluation framework for a policy research project.

- Patton, M. Q. (2021). Utilisation-focused evaluation.

- Struyk, R. (2007). Managing Think Tanks: Practical Guidance for Maturing Organizations.

- Struyk, R. (2015). Improving Think Tank Management.

- Wilson-Grau, R. (2015) Outcome Harvesting.

- Woodhill, J. (2007) M&E as learning: Rethinking the dominant paradigm.

Articles and reports

Videos

This is an introductory webinar on Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) about policy influence.