Policy relevant agendas

Trainer 2026: Áurea Moltó

Additional background material on the broader topic

Understanding public policy

Introduction

Research is at the heart of what think tanks do. But understanding the relationship between research and policy can be a bit of a puzzle. By aligning our research design and implementation with the political landscape, we can maximise the impact of think tanks’ efforts.

In this brief we explore a guiding framework and a set of principles for conducting policy-relevant research. We will also discuss various policy problems and how to approach them.

What is public policy?

Policy studies have a ‘long history and a short past’ (De Leon, 1994); while government and governance have been studied over the past millennia, the systematic examination of policies themselves as a discrete discipline dates back only a few decades. Young & Quinn (2002) sought to consolidate the different definitions of public policy into a list of key points, which are summarised below:

- Authoritative government action. Implemented by a government body with the legislative, political and financial authority to do so.

- More than an intention or promise. Policy is an elaborated approach which comprises what governments actually do, rather than what they intend to do (Anderson, 2003).

- Reaction to real-world needs or problems. Reacts to the concrete needs or problems of a society or groups within a society. Such needs or problems can be articulated as policy demands by other actors (e.g., citizens, group representatives, or other legislators) (Ibid).

- Goal-oriented. Seeks to achieve an objective or set of objectives.

- Carried out by a single actor or set of actors. It may be implemented by a single government representative or body, or by multiple actors.

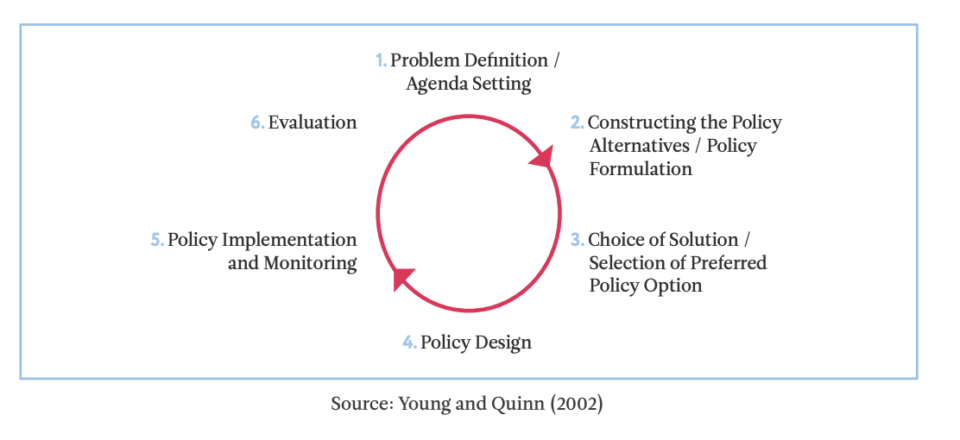

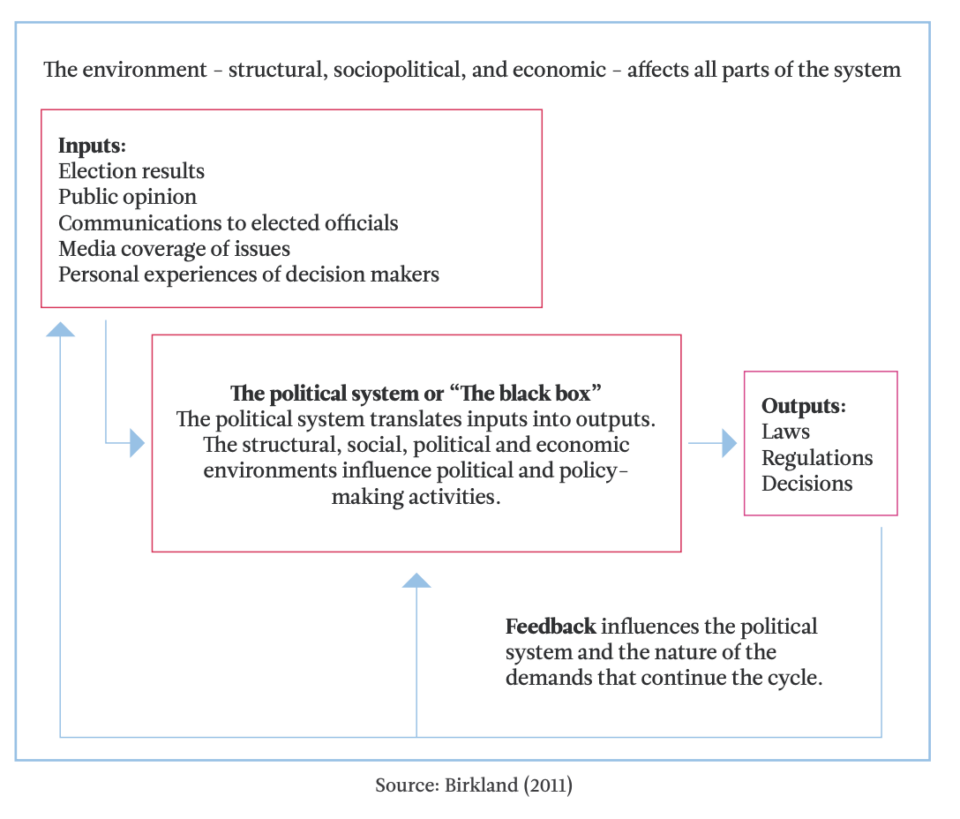

There are various models of the policy-making process which broadly describe how policy is formed and developed. These models, such as the Policy Cycle or the Black Box, often assume the policy process to be linear and simple. While such models are helpful to analyse public policy in the abstract, they can be detached from reality.

Policy cycle

Policymaking as a black box

Other ways to understand the policy process and policy problems?

- Cast from Clay’s Policy Unstuck series is a fantastic account of policymaking in real life from the point of view of the protagonists.

- The Institute for Government’s Ministers Reflect series has a huge database of interviews with UK policymakers which offers insights into their roles and the unique challenges they face.

- Oldies but Goldies is an annotated review of literature on policymaking, evidence informed policy and how to engage with policymakers.

How to align research with public policy?

Research manuals usually recommend beginning any project with a well-defined research question. However, in the search for policy relevance and influence, it may be better to take a few steps back. A useful framework to conduct policy-relevant research involves: (1) understanding the type of policy problem and (2) identifying the aim or purpose of conducting research. Only then should research questions be drafted and methodological and design choices made.

Here is a useful framework to follow:

- Define a policy problem and describe it in both technical and political terms: A policy problem is usually defined as a gap between an existing and a normatively valued situation that is to be bridged by government action (see, for example, the Areas of Research Interest platform, which shows researchers the key issues that the UK government is interested in). However, not everyone sees the same gap. And what is undesirable to some may be desirable to others. Therefore, policy problems are not constructed by only considering information or facts, but also by considering values and beliefs.

- Identify the purpose that research can play in each specific case: Once the problem has been defined ,it’s time to ask: how will research tackle the policy problem? Will research be used to find a solution, introduce an issue onto the public agenda, or facilitate a political negotiation? Research can play several roles, and researchers should be goal-oriented in choosing them.

- Formulate a meaningful research question: Once the policy problem has been clearly stated, then it’s time to draft research questions that are sharp, focused and grounded in a profound understanding of the policy problem. It is important that the questions are analytical and relate to a policy. For instance, an initial question on education could be, what is the distribution of the national budget in education? But a better question could be, how efficient is the allocation of the educational budget? Or, what rules can be used to decentralise the national budget to the provinces?

- Design a research project with your context and purpose in mind: Think about research methods as a collection of tools, each one with a particular strength. Researchers focused on informing policy should develop a variety of methodological skills to choose from, depending on the specific needs of each occasion.

Seven principles of policy-relevant research

In the previous section, we explored a framework which provides a step-by-step guide for how to conduct policy-relevant research. In this section, we present a set of principles for policy-relevant research which draw on both current literature and good practices. These principles offer overarching guidelines to cultivate the right mindset and practical skills for effective policy research.

Policy research must be:

- Embedded in the policy context: There are no clear-cut recipes, rules and standards for conducting policy-relevant research. This means that no particular type of research is in itself better than the rest. Instead, it’s important to make strategic choices by considering the context where the research is being carried out.

- Internally and externally validated: Policy-relevant research should garner acceptance both within and outside the organisation. Seeking the perspectives of others enhances the research agenda and the overall quality of each research project.

- Responsive to policy questions and objectives: Being responsive to policy questions and objectives is essential in policy research. Thus, it’s crucial to tailor research contributions to align with the specific questions and objectives of each policy problem, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all model when providing policy recommendations.

- Fit for purpose and timely: To ensure that research is ‘fit for purpose and timely’, it’s crucial to first identify the nature of the policy problem and the research questions it can address. This entails adopting a pragmatic research design approach that considers the unique characteristics of the policy problem, the available time and a think tank’s capabilities.

- Crafted with an analytical and policy perspective: Policy-relevant research goes beyond the obvious and beyond a general description of the situation. Doing the necessary homework before starting the research project and having a good sense of policy issues will help in bringing a unique perspective to the problems at stake.

- Open to change and innovation as it interacts with policy spaces and policymakers: Embracing innovation in research is crucial for a think tank to sustain its relevance in the policy process. Yet, it’s essential to strike a balance between the ability to generate new ideas and leveraging the existing capacities of the think tank.

- Realistic about institutional capacity and funding opportunities: Last, but not least, think tanks need to be realistic about what they can achieve. They should be aware of their limitations: time, resources and capacities. A well-done modest project can have more impact than an unfinished over-ambitious one.

Understanding policy problems

Types of policy problems

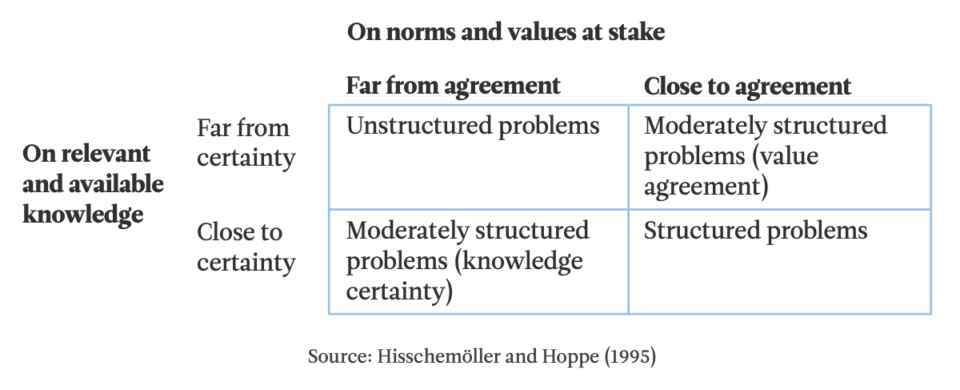

Hisschemöller and Hoppe (1995) offer a simple but powerful categorisation of policy problems (Table 1) in which two dimensions are used:

- The relevant and available knowledge: whether or not there is certainty with regard to the knowledge available about the problem.

- The norms and values at stake: whether or not there is agreement in relation to the values linked to the problem.

This classification refers to both a technical and a political (or cultural) perspective of policy problems. With these two categories in mind, four possible types of problems emerge:

- Structured problems. These are well-defined issues which often require technical expertise. They involve a high degree of consensus and clear responsibility for their resolution. Examples include regulating health services and road maintenance.

- Unstructured problems. These problems are the opposite of the former.4 They are complex, have no clear boundaries, and no specific actor responsible for solving them. There are conflicting values and knowledge that are part of an extensive debate. Examples include the consolidation or separation of states, negative impacts of new technologies, climate change, or complex democratic reform processes.

- Moderately structured problems (knowledge certainty). In these problems, there’s a certain amount of confidence regarding the technical aspect of the problem. This means that there’s certainty in relation to the knowledge needed to understand the problem. But there’s no agreement on the values associated with the problem. These include issues such as sex education in public schools.

- Moderately structured problems (value agreement). In these problems, there is consensus on the values, but no certainty about the knowledge or the technical aspects of the problem. An example of this type of problem is how to tackle the spread of HIV-AIDS or brain drain from a country. The general opinion is that these should be stopped, but there isn’t a clear understanding of why they occur or how to tackle them.

Types of policy problems

Research work will vary dramatically depending on the problem being tackled. Here are some important points to keep in mind:

- Problems are not static. In the process of understanding problems through the lenses discussed above or other lenses, you should maintain a dynamic perspective. ‘Policy problems are social and political constructs’ (Hisschemöller and Hoppe, 1995). As such, they are in constant flux.

- Decision-making involves structuring problems. For a policy to be seen as a ‘need’, the problem being faced must be structured. Often, policymakers want to know how to frame and understand a problem that would justify government intervention. This requires ensuring that the problem is communicated as clearly as possible.

- Researchers tend to problematise an issue. Researchers tend to keep finding new sides or perspectives to an issue. While that’s helpful to understand how problems are multifaceted, it may result in paralysing decision and action. It’s important to be able to handle the tension between the need to ‘structure a problem’ and the need to keep an open perspective.

REFLECTING ON HOW PROBLEMS ARE FRAMED

Before generating alternative solutions to address policy problems, it’s good to reflect on how problems are framed and understood (and the degree of consensus between the think tank and others involved).

Whose perspective is the most important when it comes to a policy problem? The think tank’s perspective or that of other stakeholders (such as the private sector, NGOs or the government)?

How can the think tank balance these different perspectives?

Should the think tank prioritise the technical dimensions of a problem or the political dimensions?

Does the think tank consciously or unconsciously shy away from certain types of problems?

How to approach different policy problems?

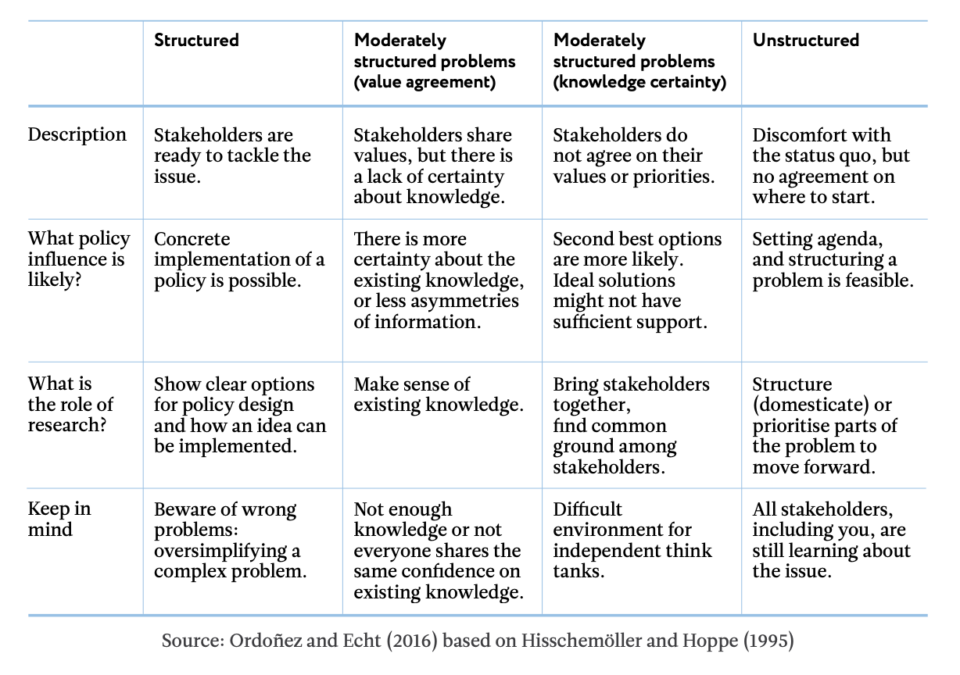

Abraham Maslow once said, ‘If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.’ If we apply this to the policy context, we can gather that different policy problems require different solutions and strategies. For each type of policy problem there are at least two key questions we can ask:

- What can a think tank realistically expect to achieve or how does a think tank seek to influence policy?

- And what is the role of research in this process?

The framework summarised in the table below presents a practical way of connecting a clear objective with the specific context and the type of research to carry out. There is a direct link between the type of problem, what is feasible to achieve in terms of policy influence, and how research can help. The framework given below is not meant to be prescriptive. While different aspects of it can be adapted, it’s important to understand the relationship between these three elements: problem–policy influence–research.

Types of problems, context and action

THINKING ABOUT POLICY AND IMPACT

The Centre for Public Impact (2016) emphasises the relationship between the technocratic and the political in their Public Impact Fundamentals framework. They identify legitimacy (public confidence, stakeholder engagement, and political commitment); policy (clear objectives, evidence, feasibility); and action (management, measurement, alignment) as drivers of what they call ‘public impact’, or ‘what governments achieve for their citizens’ (ibid.).

The website (www.centreforpublicimpact.org/) offers a variety of tools and resources. They also refer to a Public Impact Observatory, which is a database of more than 350 case studies of public policies from around the world and provides a snapshot of the policy challenge, the initiative, the public impact, and their evaluation of each across nine drivers.

Watch a video that presents this discussion:

Policy blunders and improvements

What happens when a policy goes wrong?

While it’s useful to examine instances where policymaking is successful, there’s much to be learned from the opposite case – when policymaking goes very wrong. The study of policy failures is not new (Bovens & Hart, 1995; Bovens & Hart, 1996; Dunleavy, 1995). In 2014, Anthony King and Sir Ivor Crewe released a book, The Blunders of Our Governments, that outlines what they considered to be among the most egregious of government failures – ‘policy blunders’.

Crewe (2013) defines a policy blunder as ‘a government initiative to achieve one or more stated objectives which [not only] fails totally to achieve those objectives, but in addition: Wastes very large amounts of public money; and/or causes widespread human distress; was eventually abandoned or reversed; and was foreseeable’.

Crewe distinguishes blunders from two other (lesser) types of policy failures: ‘policy disappointments’ and ‘wrong judgment calls’. A policy disappointment is where the impact of a policy ends up being smaller, slower, weaker, or costlier than anticipated. A wrong judgment call is what can happen in conditions of extreme uncertainty and lack of evidence (which can often be the case in public policymaking), and despite choosing a line of action that makes sense at the time, it turns out to be the wrong one. Policy blunders, meanwhile, are ‘sins of commission’ rather than sins of omission (Ibid.).

Causes of policy blunders can be both structural and behavioural. Structural causes relate to poorly designed processes or structures, which produce or are more susceptible to mistakes. In the British political system, Crewe (2013) identified a ‘deficit of deliberation’, meaning a lack of consultation with a range of experts and stakeholders, including those most directly affected by the policy either as recipients or implementers. Rather than arriving at a decision after a careful weighing of the pros and cons of policy options provided through consultation, British policymakers, argued Crewe, favour ‘decisiveness rather than deliberation’. This leads them to overlook issues or problems that a consultation could have unearthed.

Behavioural causes relate to an inadequacy of skills and knowledge, or even the delinquent behaviour of government officials and policymakers. One such behavioural cause is what Crewe calls ‘operational disconnect’, where ministers have little or no operational experience or knowledge, leading them to give little thought to practical implementation when designing policies (Ibid.).

How to make policies better?

While disappointment or wrong judgment calls are likely to be unavoidable in the messy world of policymaking, there are certain steps that can be taken to reduce the risk of large-scale, foreseeable policy mistakes or blunders. Taking lessons from Policy Making in the Real World: Evidence and Analysis (2011), the Institute for Government identified certain fundamentals of what a ‘good’ approach to policymaking looks like, and a checklist for how to operationalise it:

- Goals: Has the issue been adequately defined and properly framed? How will the policy achieve the high-level policy goals of the department – and the government (referencing their plans)?

- Ideas: Has the policy process been informed by evidence that is high-quality and up to date? Have evaluations of previous policies been taken into account? Has there been an opportunity or a licence for innovative thinking? Have policymakers sought out and analysed ideas and experience from others (including regional administrations and external actors)?

- Design: Have policymakers rigorously tested or assessed whether the policy design is realistic, involving implementers and/or end users? Have the policymakers addressed common implementation problems? Is the design resilient to adaptation by implementers?

- External engagement: Have those affected by the policy been engaged in the process? Have policymakers identified and responded reasonably to their views?

- Appraisal: Have the options been robustly assessed? Are they cost-effective over the appropriate time horizon? Are they resilient to changes in the external environment? Have the risks been identified and weighed fairly against potential benefits?

- Roles and accountabilities: Have policymakers judged the appropriate level of central government involvement? Is it clear who is responsible for what, who will hold them to account, and how?

- Feedback and evaluation: Is there a realistic plan for obtaining timely feedback on how the policy is being realised in practice? Does the policy allow for effective evaluation, even if the central government is not doing it? (Hallsworth & Rutter, 2011).

Final thoughts: making policies more inclusive

Policies shape the world around us, and touch nearly all areas of our lives: from the cost of taxes, to the length of our roads and highways, to the quality of our air and water, and the countries with which we choose to trade (or with whom we go to war). As is their statutory responsibility, it falls on policymakers – government officials, civil servants, ministers – to take steps to make policy better. However, ‘legitimacy’ is a key driver of effective policies, which includes public confidence and stakeholder engagement (The Centre for Public Impact, 2016). In this way, stakeholders outside of government – including civil society, think tanks, media, the private sector, and citizens themselves, including young people – all have an interest in demanding better policy, for themselves, and for society-at-large.

References and further reading

- Alain, M. (2019). Context is key – positioning your research to be useful for policy.

- Anderson, J. E. (2003). Public Policymaking: An Introduction. Boston: Houghton.

- Birkland, T. A. (2011). An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts, and Models of Public Policy Making. New York: Routledge.

- Bovens, M., & Hart, P. ‘. (1996). Understanding Policy Fiascos. New Brunswick NJ: Transaction.

- Bovens, M., & Hart, P. (1995). Fiascos in the Public Sector: Towards a Conceptual Frame for Comparative Policy Analysis. In J. J. Hesse, & T. A. Toonen, The European Yearbook of The European Yearbook of Comparative Government and Public Administration (pp. 577-608). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Cochrane, C. E., Mayer, L. C., Carr, T. R., & Cayer, N. (1982). American Public Policy: An Introduction. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Crewe, I. (2013). Why is Britain badly governed?

- Crewe, I., & King, A. (2013) The Blunders of Our Governments. London: Oneworld Publications.

- De Leon, P. (1994). Reinventing the policy sciences: Three steps back to the future. Policy Sciences, 27, 77-95.

- Dunleavy, P. (1995). Policy Disasters. Public Policy and Administration: 10:2, p. 52-70.

- Dye, T. R. (1972). Understanding Public Policy. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Fernández, R. (2011). Broad versus Narrow: Research Agendas and Economists.

- Hallsworth, M., & Rutter, J. (2011). Making Policy Better: Improving Whitehall’s core business. London: Institute for Government.

- Hisschemöller, M., & Hoppe, R. (1995). Coping with intractable controversies: The case for problem structuring in policy design and analysis. Knowledge and Policy, 8(4), 40-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02832229

- Hoppe, R. (2011). The Governance of Problems: Puzzling, Powering and Participation. Policy Press.

- Institute for Government (2011). Policy Making in the Real World: Evidence and Analysis.

- Mendizabal, E. (2013). Research questions are not the same as policy questions

- On Think Tanks series on Doing Policy Relevant Research.

- The Areas of Research Interest database.

- The Centre for Public Impact (2016). The Public Impact Fundamentals.

- Young, E., & Quinn, L. (2002). Writing Effective Public Policy Papers: A Guide for Policy Advisers in Central and Eastern Europe. Budapest: Open Society Institute.

Articles and reports

Videos

This webinar introduces a practical process for drafting policy-relevant research agendas in think tanks and research centres. It explains how to align research priorities with an organisation’s mission, capacities, and the policy context, using guiding principles such as timeliness, stakeholder validation, and fit-for-purpose methods. The session also offers frameworks to map an organisation’s policy advice functions and balance short-term responsiveness with long-term strategy, emphasising that strong research must translate into context-aware and rights-sensitive recommendations.

This webinar explains what policy-relevant research is and how think tanks can design and implement research agendas that respond to real policy problems without sacrificing analytical rigour. It outlines key differences between academic and policy research, core principles for relevance, and the importance of timing, context, and stakeholder engagement. The session emphasises research agendas as tools for change, helping organisations align mission, capacities, funding, and partnerships to effectively inform and influence policy debates.