Think tanks across the policy ecosystem

Trainer 2026: Enrique Mendizabal

Introduction to think tanks

Defining think tanks

What’s in a name?

Think tanks go by many names: think tank, policy lab, investigation centre and policy research institute/centre, to name just a few. If we add other languages and their definitions, the list is even longer: centro de pensamiento, groupe de réflexion, gruppo di esperti and many more.

The concept covers organisations with diverse characteristics depending on their origins and development pathways. Think tanks set up in the United States in the first half of the Twentieth Century are different from those set up in the latter part of the century. Think tanks also vary by country, according to the context in which they originated, and how they operate.

Their business models and organisational structures also differ greatly: for-profit consultancies, university-based research centres, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), public policy bodies, advocacy organisations, membership-based associations, grassroots organisations, one-off expert fora and more.

Despite this diversity, they all share the same objective of influencing policy and/ or practice based on research and evidence. But we also need to acknowledge that the term was coined in the United States, with an Anglo-American model in mind. This model permeates and influences think tanks in different locations in various ways. So, let’s start by reflecting on the classical definition of think tanks.

Traditional definition

Think tanks are commonly defined as organisations that conduct research to influence policies. Stone (2001) defines them as ‘relatively autonomous organisations engaged in the research and analysis of contemporary issues independently of government, political parties, and pressure groups’. This definition is widely used by think tank scholars, and it characterises them as a clearly defined type of organisation, separate from universities, governments, or any other group. But the reality is fuzzier, and think tanks that actually fit this description, like The Brookings Institution and Chatham House, are less common.

In his 2008 paper “Think Tanks as an emergent field”, Thomas Medvetz argued that the above definition is limited because it:

- Privileges the independence emphasised in US and UK traditions, which may not apply universally.

- Forgets that the earliest think tanks in the Anglo-American context were not independent, but the offspring of universities, political parties, interest groups, etc.

- Excludes many organisations that function as think tanks.

- Does not recognise the political significance of adopting/not adopting the ‘think tank’ label, which varies depending on the organisation’s political context.

Functions

Rather than pinning down a strict definition, it is perhaps better to explore the roles and functions that think tanks tend to play. Think tank roles and functions can vary based on their context, mission and aims, organisational structures, business models, and available resources. Mendizabal (2010, 2011) summarises their main functions:

- They are generators of ideas.

- They can provide legitimacy to policies, ideas, and practices (whether ex-ante or ex-post).

- They can create and maintain open spaces for debate and deliberation – even acting as a sounding board for policymakers and opinion leaders. In some contexts, they provide a safe house for intellectuals and their ideas.

- They can provide a financing channel for political parties and other policy interest groups.

- They attempt to influence the policy process.

- They are providers of cadres of experts and policymakers for political parties, governments, interest groups, and leaders.

- They play a role in monitoring and auditing political actors, public policy, or behaviour.

- They are also boundary workers that can move in and out of different spaces (government, academia, advocacy, etc.), and, in this way, foster exchange between sectors.

Think tanks may choose to deliver one or more of these functions at different times in their existence. They create spaces for engagement during polarised political climates, generate ideas for political campaigns, and offer insights during crises.

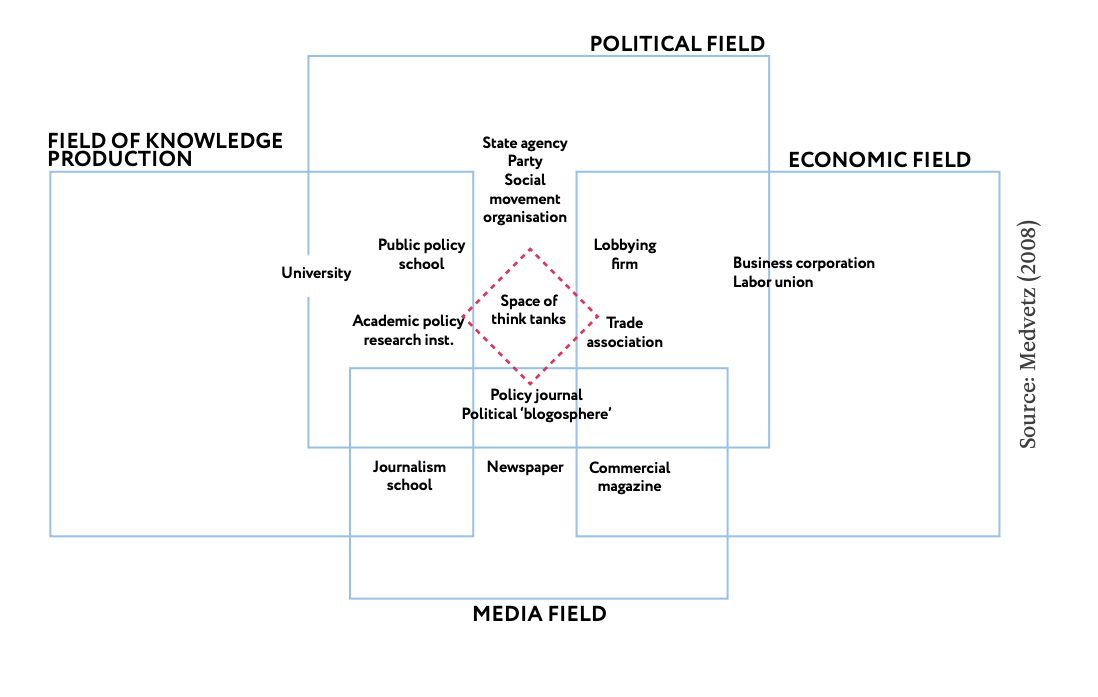

Medvetz (2008) sketched out the positions of think tanks in the social space to show that they are boundary organisations, balancing independence and connections with various actors. This dynamic view reflects how their functions evolve in response to others’ roles (see next figure).

Think tanks in the social space

Others, like Anne-Marie Slaughter (2021) have argued that the ‘think tank’ concept is outdated, covering functions no longer reflective of this century. Today, think tanks are in the problem-solving space, developing responses to social, economic and political issues. Slaughter invites us to consider a new term that reflects these functions: the change hub. Unlike a closed-off tank, a hub connects diverse actors with the shared goal of initiating ideas and action to effect change.

Towards a definition

A strict and constraining definition of think tanks is of little use. Instead, it’s more practical to embrace a broad definition that recognises the diversity in forms, affiliations, ideologies, functions, and roles within think tanks.

With this perspective, think tanks can be described as diverse entities that have as their main objective to inform political actors (directly or indirectly) with the aim of facilitating policy change and achieving explicit policy outcomes. While their decisions rely on research-based evidence, they are still influenced by values. They may perform different functions, from shaping the public agenda to monitoring policy implementation and enhancing the capabilities of other policy actors. The nature of think tanks depends on their operational context; a think tank in China won’t mirror one in Bolivia, and we shouldn’t expect them to.

This short video explains that a think tank is an organisation that bridges research and policymaking by bringing evidence-based ideas into public debate. It highlights additional roles such as convening policy actors, building capacity among practitioners and communicators, and strengthening the legitimacy of policies by backing them with research.

Think tanks as a sector

The annual Think Tank State of the Sector reports, prepared by On Think Tanks and the Open Think Tank Directory— a publicly accessible repository of over 3,800 think tanks and policy-focused or boundary organisations—provides an overview of the sector. We encourage you to explore these resources to understand the sector’s growth and trends.

Would you like to add your think tank to the directory? Register it here.

References and further reading

- Abelson, D. (2009). Do Think Tanks Matter? Assessing the Impact of Public Policy Institutes. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Balfour, R. (2017). What are think tanks for? policy research in the age of anti-expertise.

- McGann, J. and Johnson, E. (2005). Comparative Think Tanks, Politics and Public Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Medvetz, T. (2012). ‘Murky Power: ‘Think Tanks’ as Boundary Organizations’, in David Courpasson, Damon Golsorkhi, Jeffrey J. Sallaz (ed.), Rethinking Power in Organizations, Institutions, and Markets (Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Volume 34), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 113–133.

- Mendizabal, E. (2010). On the definition of think tanks: Towards a more useful discussion.

- Mendizabal, E. (2010). On the business model and how this affects what think tanks do.

- Mendizabal, E. (2011). Different ways to define and describe think tanks.

- Mendizabal, E. (2011). Think tanks: research findings and some common challenges.

- Mendizabal, E. (2013). Think tanks in Latin America: what are they and what drives them?.

- Mendizabal, E. (2014). What is a think tank? Defining the boundaries of the label.

- Mendizabal, E. (2018). What’s New in our Understanding of how Evidence Influences Policy? A view from Latin America.

- Morestin, F. (2017). The advisors of policy makers: Who are they, how do they handle scientific knowledge and what can we learn about how to share such knowledge with them? Knowledge sharing and public policy series. Montréal and Québec, Canada: National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy

- On Think Tanks (n.d.). Open Think Tank Directory.

- On Think tanks- various authors (2015). Think Tanks and their context.

- Seele, A. (2013). What Should Think Tanks Do? A Strategic Guide to Policy Impact.

- Slaughter, A. (2021). From think tank to change hub.

- Stone, D. & Denham, A. (2004). Think tank traditions: Policy analysis across nations.

- Stone, D. (2001). ‘The policy research knowledge elite and global policy processes’, in Josselin, Daphné and Wallace (eds.), No-State Actors in World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 113–132.

- Stone, D. (2005). Think Tanks and Policy Advice in Countries in Transition.

- Stone, D. (2007). ‘Recycling Bins, Garbage Cans or Think Tanks? Three Myths Regarding Policy Analysis Institutes’, Public Administration, 85(2): 259–278.

Evidence informed policymaking

For a more thorough review of the literature visit this annotated bibliography.

What is evidence-informed policymaking?

Introduction

Any discussion about think tanks is located within the space of evidence-informed policy. Especially since COVID-19, many governments have indicated their commitment to science/research/evidence use in policy; it shows up in many national policies and national development plans. But devising and implementing evidence-informed policies tend to be complex.

The policy environment is permeated by challenges, uncertainties, competing agendas and trade-offs, all of which make the area of evidence-informed policy an ongoing area of study and practice.

‘Evidence-informed policy is that which has considered a broad range of research evidence; evidence from citizens and other stakeholders; and evidence from practice and policy implementation, as part of a process that considers other factors such as political realities and current public debates. We do not see it as a policy that is exclusively based on research, or as being based on one set of findings. We accept that in some cases, research evidence may be considered and rejected; if rejection was based on understanding of the insights that the research offered then we would still consider any resulting policy to be evidence-informed.’ (Neman, Fisher & Shaxson 2012)

Systematically informing policymaking with a wide range of evidence is important and commendable, but researchers and practitioners have been increasingly moving away from the idea of evidence use as a purely technical or rational process. Scholars like Jones, Jones, Shaxson and Walker (2013), Cairney (2016) and Parkhurst (2016) have emphasised the political nature of evidence use in policy, the complexity and non-linearity of the policymaking process, and the myriad relationships (both formal and informal) that mediate the use of evidence in policy.

The growing literature on the topic generally agrees that when it comes to influencing policy, evidence:

- Will never be more than one of the inputs to the policy process – alongside ethical, fiscal, political, and other considerations.

- Does not need to be derived from experimental methods to be considered a valid input for policymaking. Jones, Shaxson and Walker (2013) for instance identified four broad and overlapping categories of evidence that are combined in policymaking processes: data, citizen knowledge, practice-informed knowledge, and research.

- Always carries a certain degree of uncertainty, even in the best of all worlds, whether on the conclusions of a study or on how to interpret results and adapt them to a different context.

- Is strongly affected and influenced by relationships between knowledge producers, brokers and users as well as relationships within all of these groups.

Moreover, the development and implementation of public policies require important knowledge of both the actors involved and the political and legal contexts, but also the expected impacts and the mechanism by which the intervention delivers its effects.

In short, the development of public policies is an area that, by nature, requires the mobilisation of a variety of knowledge types, and the purpose of promoting this approach is not to reduce the policy process to a scientific problem-solving exercise. Recognition of these realities has led to a language shift towards the use of ‘evidence-informed’ as a replacement for ‘evidence-based’ when referring to policymaking.

The relationship between policymaking and evidence

Policymaking in the real world

In 2011, the Institute for Government undertook an empirical study, Policy Making in the Real World: Evidence and Analysis to explore how policymaking practically works in the United Kingdom.6 Here are some key insights from the report, which may have broader applicability across various policymaking processes. These points are useful to consider when locating the role of evidence in policymaking, which is further discussed in the next section.

- Policy-making doesn’t happen in distinct stages. In 2003, the UK Treasury introduced a ROAMEF policy cycle (Rationale, Objectives, Appraisal, Monitoring, Evaluation, and Feedback). However, the study found that these ‘stages’ often overlap, making them hard to distinguish. Problems and solutions often arise together, leading ministers to prescribe action for unclear issues without the flexibility to make any changes.

- Policies need to be designed, not just conceived. Policy design is only one step in the policy cycle, requiring fuller consideration. The report compares it to manufacturing: ‘In business, there are quality control phases where new products are prototyped and stress-tested, before being trialled and finally going to market’ (Institute for Government, 2011). Likewise, policy proposals need extensive testing and a flexible design to adapt to local or changing circumstances during implementation.

- Policy-making is often determined by events. Policymaking doesn’t happen in a ‘black box’ or vacuum where the structural, socio-political and economic environments are exogenous to policy-making, and where governments are in total control of the process (also discussed in the background note on Policy-relevant Research). Government plans can be disrupted by unexpected events, including self-generated actions driven by a desire for media headlines or the appearance of taking action.

- The effects of policies are often indirect and take time to appear. The effects of public policies are complex, wide-ranging, and, at times, unintended – meaning that measurement and attribution can be difficult. Several models underestimate this complexity and the difficulty of tracing cause-and-effect in public affairs. They should consider interconnected policies or view policymaking as a broader systemic process.

- Existing approaches neglect politics or treat it as something to be managed. Approaches that overemphasise the technocratic aspects of policymaking (e.g., how to use evidence or build an implementation plan) undermine the impact of politics on the policymaking process (e.g., how to mobilise support, manage opposition and values, and present a vision). For example, Nicolle’s (2023) blog on policy conversations in the movie Oppenheimer explores the complex politics of evidence-informed policymaking. She also makes reference to Justin Parkhurst’s The Politics of Evidence, which offers a good starting point to understand these complexities.

How is evidence assimilated into the policy process?

Although the term ‘evidence’ is frequently encountered as claims about predicted or actual consequences – effects, impacts, outcomes or costs – of a specific action, that is only part of the story. Evidence can be used in a wide range of cases, for instance, to signal early warning of a problem to be addressed, for target setting, for implementation assessment, and for evaluation (effectiveness, efficiency, unexpected outcomes, etc.).

Evidence has five tasks related to policy: (1) identify problems; (2) measure their magnitude and seriousness; (3) review alternative policy interventions; (4) assess the likely consequences of particular policy actions (intended and unintended); and (5) evaluate what will result from policy. Thus, evidence has the potential to influence the policymaking process at each stage of the policy process – from agenda-setting to formulation to implementation. However, different forms of evidence and mechanisms may be required at each of the policy stages. In the end, whether it is data analytics, behavioural insights, horizon-scanning, or research from the ‘hard’ sciences, all these types of evidence are valid, as long as they are trustworthy and useful for governments (Breckon, 2016).

Yet, as explained previously, the policymaking process is anything but linear, and across all of these tasks, there is a wide range of political, stakeholder and value considerations that are outside the scope of evidence use, and that must be incorporated by the (multiple) actors involved in the policy advisory process.

In almost all decision-making situations, the use of evidence takes place in systems characterised by high levels of interdependency and interconnectedness among participants. No single decision-maker has the independent power to translate and apply research knowledge. Rather, multiple decisionmakers are embedded in systemic relations in which [evidence] use not only depends on the available information, but also involves coalition building, rhetoric and persuasion, accommodation of conflicting values, and others’ expectations. Evidence use is less a matter of straightforward application of scientific findings to discrete decisions and more a matter of framing issues or influencing debate’ (National Research Council, 2012).

Barriers to using scientific evidence to inform policy

The barriers to the use of evidence to inform policy have been the subject of a number of academic studies, both broadly and within specific sectors. Recent systematic reviews include those by Oliver (2014) and Langer, Tripney and Gough (2016), which outline a wide range of common barriers to evidence use, including the capacity of civil servants, access to evidence, relationships between evidence producers and users, and organisational structures and systems within government departments. Some of these factors are summarised in engaging and accessible formats by, for example, the Alliance for Useful Evidence (2016) report entitled Using Evidence: What Works? and Weyrauch et al.’s (2016) interactive Context Matters Framework.

The Context Matters Framework (2016) was developed by Politics & Ideas (P&I), a Southern–led ‘think net’ in collaboration with INASP. They used a literature review combined with more than 50 interviews with policymakers and practitioners across the Global South to map the key factors affecting evidence use in policymaking bodies. These are clustered into six interrelated dimensions, each of which contains a number of subdimensions:

- Macro context: the wider political economy context, including the political, social, economic and cultural factors that surround the policymaking institution and in which it is embedded.

- Intra- and inter-relationships, referring to the formal and informal relationships between public sector bodies as well as between government bodies and research producers and brokers such as think tanks and universities.

- Four dimensions of context within policymaking bodies:

- Organisational cultures around evidence use

- Processes and management structures

- Organisational resources (including financial but also infrastructural, e.g. IT)

- Organisational capacity

The Context Matters Framework forms the basis for participatory diagnostic processes with government agencies, which can identify which of these factors are in play in a particular context. It has been used in a range of partnerships with governments and multilateral agencies to identify and address opportunities to improve evidence use, as well as to inform conceptual frameworks to understand evidence use in policy (Langer and Weyrauch 2021).

Capabilities within government departments are one of the most fundamental factors affecting evidence use in policy. Newman, Fisher and Shaxson (2012) raised a number of key questions related to the skills and awareness of policymakers to identify their evidence needs, and to gather, appraise and use evidence in decision-making. In the UK, the Department for International Development (DfID – now FCDO) conducted an internal evidence survey in 2013 to explore its own staff attitudes and capacities towards evidence use. Later that year, DfID launched the Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence programme, a group of consortia made up of think tanks, NGOs, government departments and other stakeholders across Asia, Africa and Latin America, aiming to explore approaches to strengthening capacity for evidence use within policymaking bodies.

Beyond the issues related to internal capacity within policymaking bodies, there is also a range of practical and systemic constraints that can affect the use of evidence in policymaking. In recognition of this, efforts to strengthen capacity are typically combined with efforts to address these more systemic factors, such as the legal and regulatory environment, the resourcing of evidence collection, and the types of formal and informal relationships between evidence users and producers.

As noted above, most of the systemic constraints identified by the main literature on the issue is generally derived from, or inherent to, the broader policy environment or context. In general, the constraints associated with the policy or political environment can be summarised as follows:

- Gaps or inadequacies in terms of resources and capacities (individual and organisational) to support or stimulate evidence-informed policymaking practice.

- Political economy factors that prevent decision-makers from supporting their decisions on scientific knowledge – crises, culture, commitments, etc.

- Timeliness (or response time): either decision-makers do not seize the appropriate windows of opportunity to assimilate scientific knowledge into the decision-making process, or the data is not available in time for decision-making.

- Lack of awareness or low value given by decision-makers, or within the organisation, to scientific knowledge as an input to decision-making (no ‘demand’ from the top = no ‘incentives’ for the advisors).

- Structural issues, such as a lack of clear planning systems, procedures or practice guidelines, as well as no reinforcement mechanisms.

Government and public sector agencies around the world have recognised the need to strengthen evidence use and have invested in a wide range of structures and initiatives to improve this. Taddese and Anderson (2017) mapped over 100 different government mechanisms from around the world that seek to improve the access to and use of evidence. More recently, books by Goldman and Pabari (2021) and Khumalo et al. (2022) looked at specific African case studies including, respectively, monitoring and evaluation cultures and procedures within government departments, and evidence systems within parliaments. In the UK, reports conducted by public agencies have reviewed the use of research in the UK parliament (Kenny et al., 2017) and investigated the capability of evidence use in government (Government Office for Science, 2019). The Joint Research Centre, which supports the European Commission, published a handbook drawing on its experience to support others wishing to embed evidence in decision-making (Sucha and Sienkiewicz, 2020). And in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges convened policymakers, researchers, citizens and civil society organisations to identify opportunities for improvement in evidence use, from the global to the local level. It’s clear that collaboration and co-creation are key to the future of advancing evidence-informed policymaking, and that think tanks have a critical role to play in this.

References and further reading

- Alliance for Useful Evidence. (2016). Using Evidence: What Works?.

- Breckon, J. (2016). Evidence in an era of ‘post-truth’ politics.

- Broadbent, E., Moncada, A., Echt, L., Weyrauch, V. and Mendizabal, E. (2013). Research and policy. Global Development Network Topic Guide.

- Cairney, P. (2016). The politics of evidence-based policy making.

- The Evidence into Action Team, (part of the Department for International Development, DfiD which is now known as the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, FCDO). (2013). DfiD Evidence Survey.

- Du Toit, A. (2012). Making sense of ‘evidence’: Notes on the discursive politics of research and pro-poor policy making’.

- Global Commission on Evidence. (2022). Global Evidence Commission Report.

- Goldman, I. and Pabari,M. (2020). Using Evidence in Policy and Practice: Lessons from Africa.

- Institute for Government (2011). Policy Making in the Real World: Evidence and Analysis.

- Head, Brian. (2016). Toward More “Evidence-Informed” Policy Making?.

- Hyder et al. (2011). National policy-makers speak out: are researchers giving them what they need?

- Institute for Research on Public Policy & Canadian Academy of Engineering – IRPP-CAE, (2016). Round Table Report: Making Better Use of Science and Technology in Policy-Making.

- ITAD. Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) evaluation.

- Jones, Jones, Shaxson and Walker. (2013). Knowledge, policy and power in international development: a practical framework for improving policy.

- Khumalo et al. (2002). African Parliaments Volume 2: Systems of Evidence in Practice.

- Kenny et al. (2017). The Role of Research in the UK Parliament.

- Langer et al. (2016). The Science of Using Science.

- Langer, L. & Weyrauch, V. (2021). Using evidence in Africa: A framework to assess what works, how and why.

- Mayne, R., Green, D., Guijt, I., Walsh, M., English, R. & Cairney, P. (2018). Using evidence to influence policy: Oxfam’s experience.

- Newman, Fisher & Shaxson. (2012). Stimulating Demand for Research Evidence: What Role for Capacity-building?.

- National Research Council (2012). Using Science as Evidence in Public Policy.

- Nicolle, S. (2023). From screen to sector: Four policy conversations in Oppenheimer.

- Oliver et al. (2014). A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers.

- Parkhurst, J. (2017). The Politics of Evidence: From Evidence-Based Policy to the Good Governance of Evidence.

- Prewitt, K., Schwandt, T.A, & Straf, M.L. (Editors) (2012). Using Science as Evidence in Public Policy, Committee on the Use of Social Science Knowledge in Public Policy. National Research Council, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

- Sir Gluckman, P. (2019). Principles of science advice & understanding risk within that context.

- Sucha, V. and Sienkiewicz, M. (2020). Science for Policy Handbook.

- Taddese, Abeba and Anderson, K. (2017). 100+ Government Mechanisms to Advance the Use of Data and Evidence in Policymaking: A Landscape Review.

- UK Government Office for Science. (2019). Government Science Capability Review.

- Vogel, I. & Punton, M. (2018). Final Evaluation of the Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) Programme.

- Weimer, D. L., & Vining, R.V. (2005). Policy Analysis. Concepts and Practice.

- Weyrauch et al. (2016). Context Matters Framework.