Governance, management and organisational culture

Trainer 2026: Sonja Stojanović Gajić

Additional background material on the broader topic

A focus on formal and explicit aspects of governance and management

Definitions

The governance and management of think tanks and policy research organisations is a complex matter. There are many aspects to consider; for example, the context in which a think tank operates and the business models that it operates under. And while there isn’t a one-size-fits-all model, there certainly are some lessons that organisations in all contexts can benefit from.8

Although governance and management concerns are often at the top of the list of challenges for any think tank leader, few efforts are aimed at strengthening them; rather, think tanks (and funders) often pay greater attention to fundraising, research quality and communications. Governance and management issues are not usually considered until a big crisis arises – usually because of not having invested in these areas before or not noticing the symptoms early enough. Without an appropriate governance arrangement and management competencies, think tanks are unlikely to be able to deliver sustainable funding strategies, high-quality research, and effective communications.

What forms of governance and management exist? How do they affect a think tank’s work? How can they drive high-quality research and policy influence? This note provides an outline of the topic and suggests several resources to engage with the issue further.

What does governance and management involve?

The governance of a think tank refers to its organisational arrangement and how decision-making processes take place. It involves the rules and norms of the interactions within the organisation that affect how different parts are brought together. Management, on the other hand, involves the practical aspects of the organisation’s functioning: team and project management, staffing, line management and so on (Mendizabal, 2014).

A think tank’s set-up can mark the difference between success and failure – a proliferation of outputs and success in influencing policy is only temporary if the internal structure of an organisation is not strong. For instance, think tanks need a strong, competent and committed board to steer them through choppy waters. A weak board will miss the tide, it will not be able to support its director (it may not even be able to appoint the most appropriate director), won’t be able to invest in long-term initiatives or in new skills for future challenges. Even a well-funded and very visible organisation is at risk if it has a weak board.

This note will address two crucial elements of governance and management: boards and management for research.

Think tank boards

To address the characteristics of each type of board, one must first acknowledge that there are different kinds of think tanks: from independent civil society think tanks established as non-profit organisations, through governmentally created or state- or party-sponsored think tanks, to policy research institutes located in or affiliated with a university and corporate-created or business-affiliated think tanks.

The nature of each think tank can say a great deal about their governance structure. For example, state-sponsored think tanks most probably will not have, nor need, the same type of board that an independent civil society think tank or a political party think tank has. Think tanks can all also have secondary boards such as advisory boards or management committees. Think tanks with a strong academic foundation might not need an advisory board, but others may use them to gain academic credentials.

Several factors such as the legal, economic, political and social context of a nation can also influence the way a think tank’s board is set up.

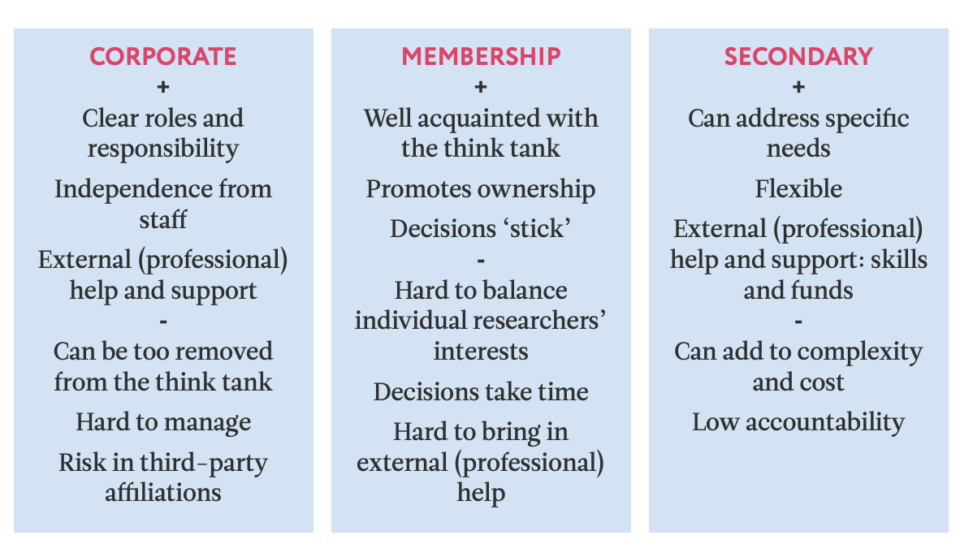

On Think Tanks identifies three main types of boards (Mendizabal, 2014): corporate boards, membership boards, and secondary boards.

- Corporate boards: A corporate board of directors is in charge of mainly two tasks: defining and maintaining the think tank’s original goals and values, and determining and ensuring its finances. According to Struyk (2012), a corporate board’s role has three aspects: legal, functional and symbolic. In that sense, they share similarities with boards in for-profit organisations. They can also be referred to as legal boards, as their responsibility for the finances and appropriate functioning of the think tanks they govern is determined by their country’s legislation.

This type of board of directors usually has the responsibility of appointing an executive director, who in turn has the responsibility of appointing and overseeing the staff and all the think tank’s day to day activities. The ODI Global in the UK and Grupo FARO in Ecuador have corporate boards.

- Membership boards: Some think tanks establish assemblies consisting of all associates of the organisation, usually its researchers and founding members. This assembly is the highest governing body and periodically meets and chooses an executive council, either from within the members or from the outside. The assembly then delegates many executive responsibilities to the executive council, which acts as a management committee in charge of the organisation’s day to day activities. In some cases, the executive council appoints an executive director and in other cases it chooses one from among its own ranks. The Instituto de Estudios Peruanos in Peru has a membership board.

The membership board is often referred to as a political body, as the leaders are elected by the members rather than interviewed for a job.

It is possible for both models to be combined, dividing ‘political’ responsibilities (membership boards) from ‘executive’ ones (corporate boards).

- Secondary boards: Think tanks may have a board of directors, either corporate or membership, and a second body that supports it. They may, for instance, have a management committee made up of members of the board in the form of a sub-committee to advise and monitor the executive director, or in some cases even be in charge of managing the think tank. Secondary boards differ from the board of directors because they have a more day-to-day role in the organisation’s activities.

There are also advisory boards. These are usually made up of highly specialised individuals who have experience in an issue that the think tank wants advice on (for example, the public sector or academia). These boards give guidance, for example, on the types of research that the organisation should undertake. Unlike the board of directors, advisory boards do not have fiduciary responsibility and so are not responsible for the institution’s audit or the state of its finances. Advisory boards that are comprised of eminent scholars and professionals may even add prestige to the organisation.

Pros and cons of board models

Management for research teams

Management overlaps with governance in that it reflects the nature of the organisational arrangement that the think tank has established for itself. It is affected by, and affects, for example, the presence of a senior management board, middle-management roles (for example, department or programme leaders), and the degree of responsibility awarded to the executive director.

This section discusses management for research, i.e., the roles and responsibilities that research teams may be awarded, including line management considerations.

Management for research involves at least two key elements: research team structures (how the think tank organises its research teams and how the teams themselves are organised) and line-management within research teams and projects.

Research team structures: According to Struyk (2012), think tanks can choose from one of two extremes: team or solo star. The ‘solo star’ model is based on the presence of notable and influential researchers who work on their own with the support of research assistants; the team model is very much what it sounds like – research conducted by teams.

Each model has consequences on the kind of work the think tank is able to deliver. The solo star model is likely to involve shorter or single research projects, while the team model is likely to involve longer-term and larger-scale programmes.

In practice, think tanks organise their research teams in various ways. Four approaches have been identified:

- Associates on short-term contracts from the think tank.

- Researchers working on their own policy research agendas with or without thematic coordination and with the support of assistants and associates.

- A central and permanent pool of researchers with specialist senior researchers who focus on one or more policy research agenda or project.

- Research teams, departments or areas organised by discipline or policy issue with clear line management.

The choice of model, according to Struyk, is likely to be influenced by several factors, including the type and size of projects, variability of the workload, flexibility of the staff, tax and social fund consequences, and institutional reputation.

Similarly, think tanks that group their researchers in teams may prefer to organise them along disciplinary or policy lines. For instance, some think tanks have departments that reflect the disciplinary background of their researchers: economics, political science, natural resources, etc. Others prefer departments focused on policy issues or challenges: housing reform, corruption, urban poverty, etc.

Line management: Line management arrangements and processes are crucial to guarantee the effective functioning of teams and think tanks. They refer to the chain of command and relations of hierarchy within a think tank and a team. Even in circumstances in which researchers act rather independently from each other or from the organisation, or in horizontal business models, a minimum degree of leadership and line management are necessary.

Line management should focus on the most effective allocation of human resources to deliver the organisation’s mission, on supporting those resources, and on enhancing their capabilities. Good practice and literature on the subject suggest some of the following considerations in developing appropriate line management arrangements to lead and support teams and projects:

- Guidelines at the ODI Global suggested that no manager should line-manage more than five people.

- Line management roles should be adequately resourced with enough time allocated to managers to work with and support their teams.

- Line management choices should not be driven by seniority imperatives but by the most effective use of talent to deliver project, programme and organisational objectives. Often, senior and experienced researchers can play important roles as members of a team, and not necessarily as their leaders.

- Line management tools such as staff performance assessments should be used primarily to support staff development and overall team performance rather than for accountability purposes.

- Depending on the composition of teams, line management arrangements could include multiple management hierarchies. For example, a young researcher could be line managed by the leaders of more than one project (in a solo star model) and, similarly, a communications officer could be line managed by a research programme leader and the head of communications.

References and further reading

- Cahy, E. & Echt, L. (2015). Unravelling the business models of think tanks in Latin America and Indonesia.

- Gutbrod, H. (2017) Developing a portfolio of services: unique, repeatable, profitable and willing to pay.

- Iyer, R. (2019). Key elements of the talent agenda – attracting and retaining staff.

- Lucas, S. & Taylor, P. (2019). Strengthening policy research organizations – what we’ve learned from the Think Tank Initiative.

- MacDonald, Levine (2008). Learning While Doing: A 12-Step Program for Policy Change. Mendizabal, E. (2014). Better Sooner than Later: Addressing think tanks’ governance and management challenges to take full advantage of new funding and support opportunities.

- On Think Tanks series on Governance and Management.

- Ralphs, G (2016a).Think tank business models: The business of academia and politics.

- Ralphs, G. (2016). Think tank business models: Are think tanks a distinctive organisation type?

- Stone, D. & Denham, A. (2004). Think Tank Traditions: Policy Analysis across Nations.

- Struyk, R. (2012). Managing Think Tanks: A practical guide for maturing organisations.

- Struyk, R. (2015). Improving Think Tank Management: Practical Guidance for Think Tanks, Research Advocacy NGOs, and Their Funders.

- Tolmie, C. (2015). Context matters: so what?

- Varga, S. (2019). Business development in think tanks – who deals with what?