Fundraising strategies for uncertain times

Trainer 2026: Goran Buldioski

A funder’s perspective on the think tanks sector – fundraising strategies for uncertain times

Fundraising has always been more of an art than a science. In this session with Goran Buldioski, we will

delve into the unique perspective of funders in the think tank landscape. We’ll explore how funders

evaluate projects, prioritise initiatives, and measure impact. Participants will gain valuable insights into the

motivations and expectations of funding organisations and the latest trends in the funding landscape. By

the end of the session, we expect participants to have a better understanding of the challenges of aligning

funders’ priorities with their think tank’s mission.

Additional background material on the broader topic

Introduction to funding models and strategies

Funding is a key concern for every think tank, affecting its sustainability, the way people work, and the type of research that is conducted, as well as the potential for having sustained policy influence.

Even though there are plenty of capacity-building activities that focus on how to carry out effective fundraising, little has been done in terms of systematising the diverse range of existing funding models, along with their implications and consequences on think tanks’ performance, relevance, identity and sustainability.

There is also increasing interest from think tanks in understanding how to develop or strengthen domestic support for their work or create new sources of income, often recognising that they rely too heavily on international cooperation or on conducting isolated projects under a consultancy model.

To complement this introduction, we invite you to explore this video:

This section helps systematise aspects of different funding models and analyses their implications and consequences. More specifically, it seeks to:

- Raise awareness on the different ways of generating and using funding and their respective implications for the organisation and its members; and

- Share ideas and innovative practices for managing diverse funding models.

Funding models

What is a funding model?

Let us start with an exploration of what a funding model is. One useful definition holds that ‘it is a methodical and institutionalised approach to building a reliable revenue base to support an organisation’s core programmes and services’ (Kim, Perreault and Foster, 2011). The most important bits of this definition are probably the first two: a methodical and institutionalised approach.

This might seem obvious, but: How many think tanks have developed a sound and thoughtful (methodical) funding strategy, which guides fundraising efforts and ensures that there is consistency between the sources of revenue, quality of research, and policy influence capacity? Are fundraising efforts often guided by strategic planning and long-term thinking? How internally driven are these efforts vis-à-vis responding to the external demands and opportunities?

Indeed, the second part of the definition, an institutionalised approach, highlights the connection between funding and the organisation’s mission, which is pursued through its programmes and services. This is where the concept of business model can become useful, since the think tank needs to clearly understand what it offers to core stakeholders (business model) to then detect who can support this effort (funding model).

What does success look like?

In line with the definition provided, a successful funding model is one that creates sustainable revenue in a way that enables the organisation to best pursue its mission. This idea can be broken up into five basic components so that one can assess the current degree of success:

- Reliability: Funds that come and go ‘randomly’ can never help the organisation in the medium and long term. In this light, unusually high growth is no indication of having an efficient funding strategy, nor does some seasonality in revenues mean the opposite.

- Diversification: Not surprisingly, putting all the eggs in one basket is not advisable. Diversifying does not only mean trying to have many donors, but also different types of donors, whose downturns should not be expected to coincide.

- Acceptable conditions: Whatever administrative, contractual and/or programmatic conditions are attached to funds, they should enable the think tank to do their policy work to the best of their abilities.

- Independence: A basic condition of a good funding model is for it to guarantee that a think tank remains independent to govern itself and define its policy research agenda: deciding how to run the organisation, which issues to pursue, etc.

- Transparency: A growing concern related to funding models has to do with being able to track the origin of funds that think tanks receive and the main conditions attached to them.

Different funding models and their implications

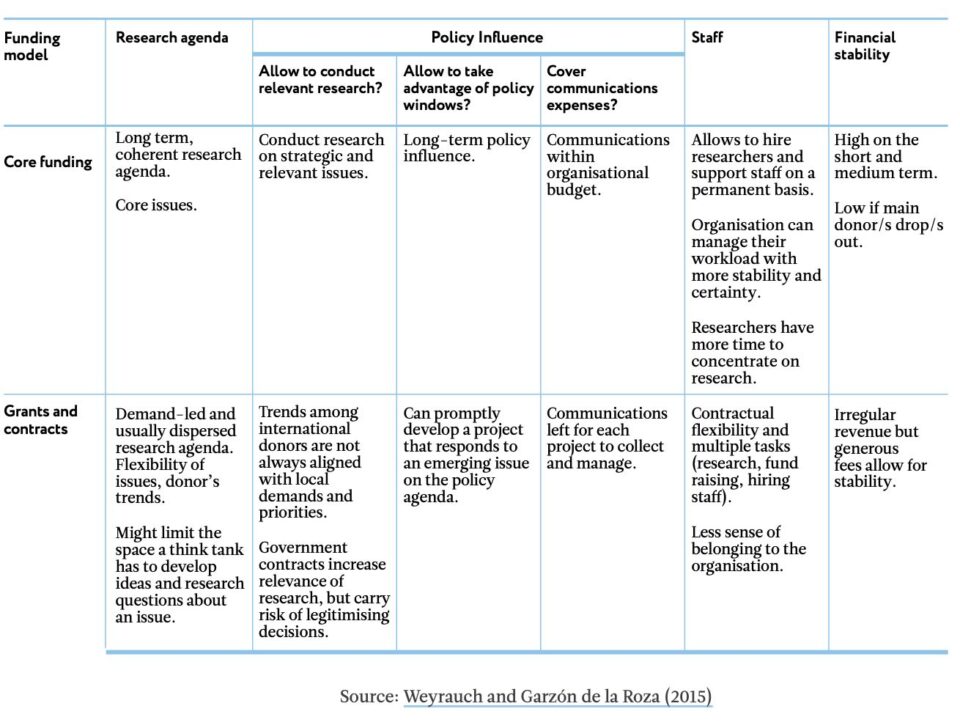

Think tanks have found unique answers to the question of funding. Among the main sources of funds, the most recurrent ones are core funding and contracts (and grants). It is the specific combination of these sources and how they interact with a think tank’s work that ultimately defines a funding model.

It is also important to think about the implications of these funding models on three functions that most think tanks regard as essential to their mission: research, policy influence, and communications. The implications on financial stability should also be considered. Raising awareness on these implications is a first step to assess how appropriate the current funding model is for the way think tanks want to conduct research, communicate with key stakeholders, and influence policy. In fact, not making these links more explicit and avoiding deep organisational discussions about them deters a think tank from the possibility of re-thinking about the viability and soundness of its intended identity (mission, objectives, main attributes and values, etc.).

The table below sets out some of these considerations for two main funding models.

Funding models can help develop evidence-informed fundraising strategies:

The fundraising function: How to organise it and why?

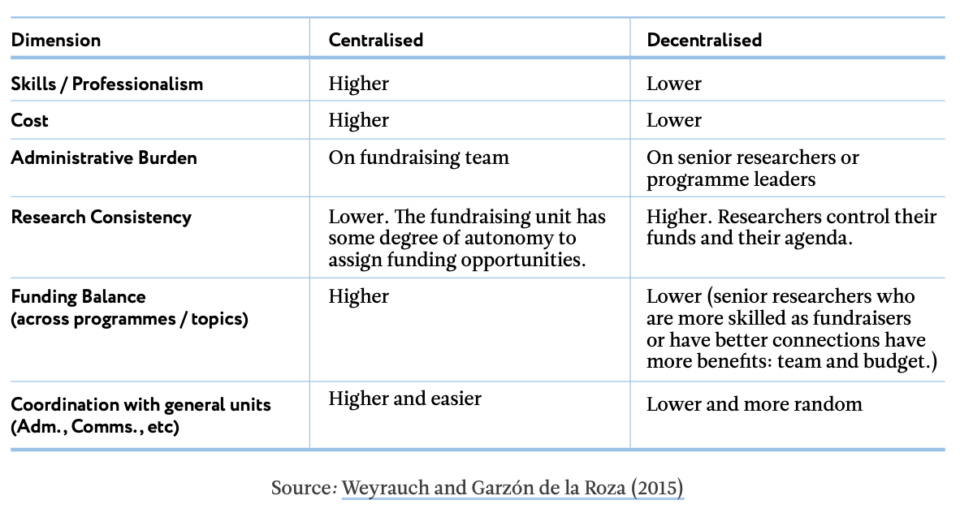

In most think tanks starting out, one is likely to find two scenarios regarding the fundraising function. In both there is a group of policy researchers/entrepreneurs that set up the organisation, often around one or a couple of leaders. In one scenario, incoming projects are found and managed by the leader or main partners in the nascent think tank. The organisation’s funding fate is tied to their connections and initiative. In the other scenario, the same group is supported by an endowment or core grant from a single donor. In consequence, fundraising is restricted to managing the practicalities of the grant and the relationship with the donor more generally (based on Telgarsky, 2002).

Some organisations can preserve such schemes for several years without any strong incentive to change. As long as the think tank keeps its founders, partners or key members, approaching funders and deciding how to use funds can remain manageable for this small group. If the organisation grows substantially, however, the fundraising function will probably look different: more formal staffing arrangements, more substantial fixed costs related to facilities and administration (e.g. office space, accounting, and legal procedures), and greater costs for business development. Hence, the organisation increasingly spends time and resources collecting information, writing proposals and raising funds.

The following table compares the funding arrangements that are likely to emerge – centralised versus decentralised.

For an applied perspective on navigating these implications, explore this video:

Why re-think the funding model?

Even if uncertainty, tensions and questions regarding funding will always be a part of a think tank, it is important to re-think the funding model every once in a while. This entails first making the model clearer and explicit for members of the organisation as well as relevant stakeholders, and then reflect on it. Here are some reasons for clarifying a funding model, and based on that, deciding what changes should be made:

- Ensures that the organisation has a fairly logical and internally consistent approach to its operations and that this approach is clearly communicated to its stakeholders.

- Provides an architecture for identifying key variables that can be combined in unique ways, hence a platform for innovation.

- Develops and strengthens a vehicle for demonstrating the economic attractiveness of the organisation, thereby attracting donors and other resource providers (Zott and Amit, 2010).

- Provides a guide to ongoing organisational operations, including parameters for determining the appropriateness of various strategic or tactical actions that management might be considering.

- Facilitates necessary modifications as conditions change.

Consider the next video from a past School:

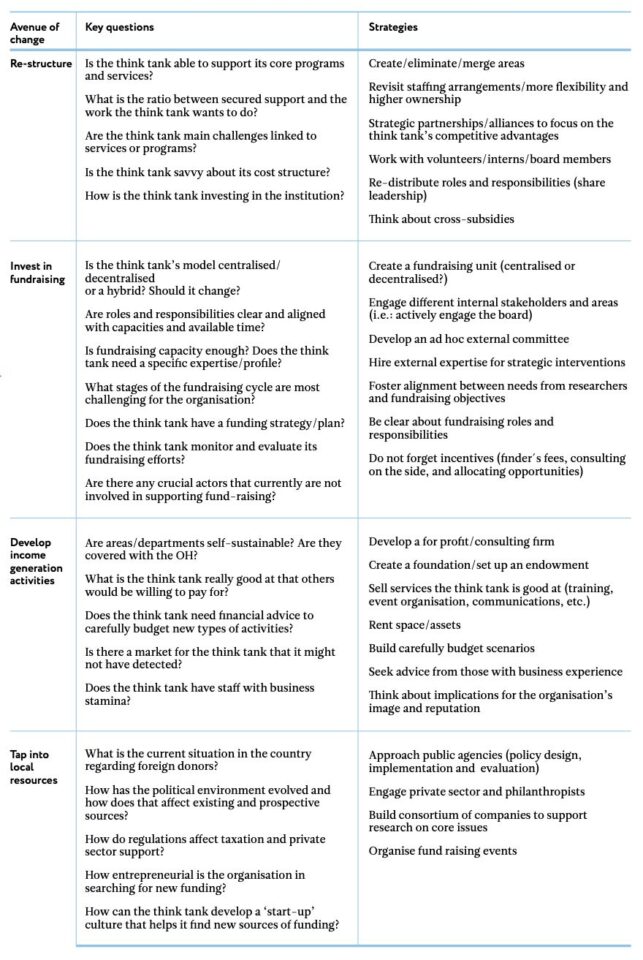

Exploring avenues of change

When looking for ideas to introduce changes in a funding model, it is better to respond to the challenges of the context (both external and organisational) and begin by exploring these four avenues of change:

Additional videos from past School trainers and think tank experts

Also see this OTT talk on fundraising challenges and opportunities for think tanks.

References and further reading

- Cahyo, E. and Echt, L. (2016). Unravelling Think Tanks’ Business Models.

- Galvin, C. (2005). Global Development Network (GDN) Toolkit: Proposal writing and fundraising.

- Kim, P., Perreault, G., & Foster, W. (2011). Finding Your Funding Model: A Practical Approach to Nonprofit Sustainability.

- Levine, R. (2019) Webinar: The think tank-funder relationship.

- Telgarsky, J. (2012) Financial Management: Sustainability and Accountability. In Struyk, R. Managing Think Tanks: A practical guide for maturing organisations.

- Mendizabal, E. (2010). On the business model and how this affects what think tanks do.

- On Think Tanks section on funding for think tanks.

- Ralphs, G. (2011). Thinking through Business Models. Reflections on Business Models for Think Tanks in East and West Africa.

- The Open Think Tank Knowledge Platform. How to develop a business plan and what it should entail.

- Zott, C. and Amit, R. (2010). Designing your future business model: An activity system perspective.